A research team has cast fresh light on how eukaryotic cells integated bacteria in the course of evolution to become organelles, thanks to a study of the single-celled flagellate Angomonas deanei, which contains a bacterium that was taken up relatively recently.

In the journal Current Biology, the biologists from the Institute of Microbial Cell Biology at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf (HHU) describe how certain proteins in the flagellate control the cell division process of the bacterium, among other things.

In the course of evolution, modern eukaryotic cells (cells with a nucleus), have taken up bacteria from their environment. The cells have brought the incorporated bacteria under their control and now utilise them for important functions such as metabolic processes. The bacteria have thus become cell organelles such as mitochondria, the “powerhouses of the cell”, and chloroplasts, in which photosynthesis occurs in plants. This happened around 1.5 to 2 billion years ago.

Organelles, whose bacterial predecessors possessed their own genetic material, have significantly reduced their genome, meaning that they have become increasingly dependent on the host cell over time. Their metabolism, protein composition and reproduction are now largely controlled by the host organism.

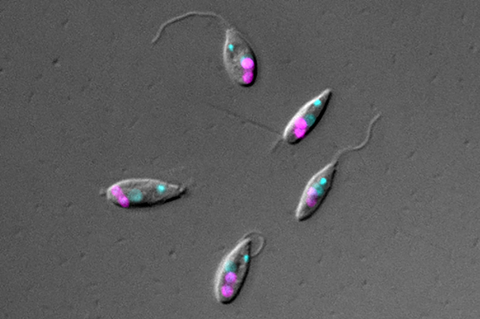

A working group headed by Professor Dr Eva Nowack from the HHU Institute of Microbial Cell Biology examined Angomonas deanei, a flagellate that lives in the intestines of insects. This model organism is particularly well suited to the study as every one of these single-celled organisms contains just one symbiotic bacterium, which was incorporated in relatively recently (between 40 and 120 million years ago). This bacterium supplies the host with vitamins and certain metabolites.

Similar to mitochondria and chloroplasts, the genome of the bacterium is already reduced compared with its free-living relatives, but not yet to the same extent as in conventional organelles. The integration is however sufficiently advanced for cell division to occur synchronously: When the host organism divides, so does the bacterium – just once, with one part going into each new flagellate cell.

Controlling the endosymbiont

The Düsseldorf research team wanted to find out how the host cell controls the endosymbiont. They examined its protein composition and discovered that a certain number of proteins from the host cell are transferred to the endosymbiont. Three of these proteins form a ring around its division site.

The researchers were able to predict the function of two of these proteins by comparing them with known protein sequences. One of them is similar to the protein ’dynamin’, which can polymerize into contractile helical chains. A further protein, the peptidoglycan hydrolase, is known to be able to break down bacterial cell walls.

In mitochondria and chloroplasts, dynamin-like proteins also form a ring around the organelle division site and the contraction of this ring aids the fission of the organelles. In addition, the division of some chloroplasts requires a peptidoglycan hydrolase to break down the remnants of the bacterial cell wall at the division site of these organelles.

Professor Nowack says: “Our work shows that a eukaryotic host cell can transfer certain proteins to the endosymbiont at a relatively early stage in the evolution of an endosymbiotic relationship. These proteins enable the cell to gain control over the symbiont.”

Jorge Morales, Georg Ehret, Gereon Poschmann, Tobias Reinicke, Anay K. Maurya, Lena Kröninger, Davide Zanini, Rebecca Wolters, Dhevi Kalyanaraman, Michael Krakovka, Miriam Bäumers, Kai Stühler and Eva C. M. Nowack: Host-symbiont interactions in Angomonas deanei include the evolution of a host-derived dynamin ring around the endosymbiont-division site, Current Biology

No comments yet