Ocean pollution is widespread and worsening by the day. From oil spills to garbage accumulation in the Pacific, marine ecosystems are in dire need of a solution.

Bioremediation that uses marine microbes looks promising due to these microbes’ unique adaptations to the aquatic environment. Such measures integrate naturally occurring and human-introduced microorganisms to combat contaminants and leave polluted sites cleaner than before.

The application of bioremediation technologies requires comprehensive research and understanding of microbial functions to successfully maximize their usefulness.

The scope of ocean pollution

On April 10, 2010, the Deepwater Horizon rig exploded in the Gulf of Mexico, dumping 60,000 barrels of crude oil into the ocean per day for 87 days — totaling 134 million gallons of oil by the end of the disaster. Responders only recovered 16% of the oil, while winds and ocean currents caused half of it to spread along more than 1,300 miles of shoreline with fatal consequences.

The event — named the worst oil spill in U.S. history — ravaged coral reefs, sea turtles, marine mammals, and fish populations as the oil swept across the ocean floor and spoiled saltwater marshes and beaches. Many animals ingested and inhaled the oil as they swam through it — killing or polluting billions — and the oil also posed a risk to people’s health.

However, oil and petroleum byproducts are only a few of the major pollutants found in marine habitats. Human activities have littered the ocean with macro- and microplastic pollution, heavy metals, industrial chemicals, and agricultural runoff, including pesticides and fertilizers.

These contaminants severely disrupt marine microbial communities and biogeochemical processes. For example, oil and plastics hinder biodiversity by introducing invasive carbon sources, which harm essential microbes capable of degrading hydrocarbons and plastics.

Heavy metals suppress microbial activity by poisoning vulnerable species, while agricultural runoff fuels toxic algal blooms. The algal blooms deplete nutrients, cause dead zones through hypoxia, and release toxins that are lethal to marine wildlife.

Interactions between microorganisms and toxic algae can also alter microbial physiology and change their abundance and nutrient-cycling functions during different bloom stages. The shift can negatively impact oxygenation and the decomposition of organic matter, which ensures a healthy marine ecosystem.

Scientists are exploring native, acclimated marine microbes for bioremediation of ocean pollution. These microbes are highly effective in natural attenuation, in which they break down pollutants into less harmful substances.

Examples of marine microbes as bioremediation agents

The ocean contains millions of marine microorganisms with impressive bioremediation capabilities. They’re a sustainable option for eliminating pollutants and safeguarding fragile aquatic ecosystems and wildlife. Using marine microbes is also more cost effective than traditional remedial methods, guaranteeing healthier oceans and robust biodiversity. Here’s how they work.

Hydrocarbon bioremediation

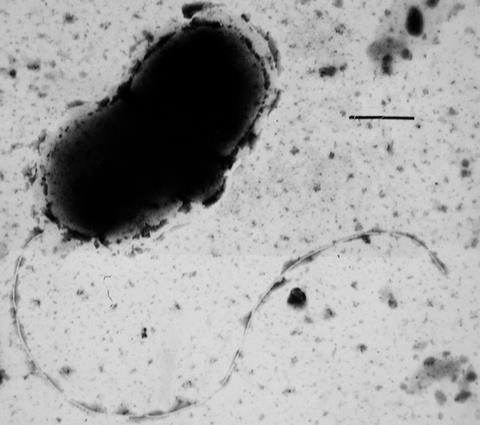

Researchers have extensively studied hydrocarbonoclastic bacteria like Alcanivorax, Pseudomonas and Marinobacter and their ability to degrade alkanes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons found in crude oil, gasoline and coal.

Micrococcus luteus and M. yunnanensis help clean oil spills. According to one study, M. luteus removed 98.97% of the oil in 144 hours, while M. yunnanensis removed 97.77% in the same time frame.

Biosurfactants play a critical role in the biodegradation of oil by emulsifying the oil for easier degradation. They also hasten the biodegradation of biomass and help dissolve the droplets in water.

Plastic degradation

Plastic pollution is among the most difficult type of pollution to eradicate. However, polyethylene terephthalate hydrolase (PETase) and mono-(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate hydrolase (MHETase) — which bacteria and fungi like Ideonella sakaiensis release — can break down polymers into more manageable forms.

PETase first breaks down PET into mono-terephthalic acid. The MHETase then degrades it further into terephthalate and ethylene glycol, which bacteria can easily metabolize as carbon. There was much excitement about this discovery, as it suggested the enzyme could solely survive on PET as a food source.

Of course, microbes can only do so much to address plastic pollution. Oftentimes, efforts result in only a partial degradation, leaving fragments behind. The process is also much slower than conventional plastic waste management solutions and is difficult to scale. Furthermore, the enzymes are susceptible to varying environmental conditions that may disrupt the process.

Heavy metal bioremediation

Desulfovibrio and Shewanella play key roles in removing heavy metals from the ocean. They utilize different mechanisms — biosorption, bioaccumulation, and biotransformation — to bind, sequester, and convert metal compounds and reduce them to less hazardous or soluble forms.

Industrial activities and mining are primary sources of heavy metals in the ocean, but they may also occur naturally. Scientists have studied Desulfovibrio’s sulfate-degrading mechanisms, especially to reduce or eliminate copper, chromium, manganese, iron, zinc, cadmium, and lead. These compounds can harm enzymes’ catalytic activity and cellular organization, hindering plants’ growth and metabolism.

Researchers have also explored using attapulgite clay in conjunction with bioremediation to remove mercury. Attapulgite derives from marginal marine zones — like saltwater marshes, tidal flats, estuaries, and bays — and has valuable absorbing abilities. It’s even proven effective at removing most per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances when its surface is chemically modified.

Nutrient removal

Agricultural runoff contains nitrogen and phosphorus to help crops grow. Yet, these are also key ingredients in eutrophication and algal blooms. Fortunately, marine microbes can mitigate the effects by removing these components through various mechanisms.

For instance, heterotrophic nitrifying and aerobic denitrifying microorganisms — like Pseudomonas and Paracoccus — transform harmful nitrogen into non-toxic nitrogen gas, preventing dead zones where marine life can no longer survive.

Meanwhile, the bacteria Brocadia directly converts nitrite and ammonium to gaseous nitrogen through annamox. According to one study, anammox can remove up to 50% of nitrogen from marine ecosystems, exceeding denitrification.

Additionally, phosphate-accumulating organisms — such as Acinetobacter — sequester and store phosphorus in wetlands, where microbes eliminate nitrogen and phosphorus from agricultural runoff before it empties into the sea.

Strategies for enhancing marine microbial bioremediation

Although marine microbial bioremediation is naturally effective at cleaning up ocean pollution, there are strategies to enhance the outcome, such as the following:

- Bioaugmentation: introduces distinct, propagated microorganisms to microbial communities in contaminated water to boost pollution degradation

- Biostimulation: delivers nutrients to existing microbes so they can break down substances more efficiently, similar to fertilizing soil

- Genetic engineering: manipulates marine microbes’ DNA to supercharge their efficiency in breaking down plastic and oil and absorbing more heavy metals

- Consortia engineering: combines multiple microbes to make pollution cleanup more efficient

These techniques aren’t without shortcomings, of course. Although bioaugmentation is promising, the planted bacteria may experience a washout before they can adapt to their new environment. Likewise, genetic engineering has long raised ethical concerns across the scientific community and the general public, such as whether it drives genetic diversity loss or disrupts the natural ecology by targeting the wrong organisms.

Challenges and considerations

The world must address ocean pollution quickly, as contaminants directly harm marine species, destroy critical habitats, reduce fish populations, and potentially accumulate in the food chain. The impacts could further hurt coastal communities economically by affecting the tourism sector and causing a public health crisis. Some regions even rely on healthy fish populations for food security and their livelihoods.

While bioremediation using marine microbes is a sound approach to addressing the large amounts of chemicals and debris across the aquatic environment, there are challenges and considerations researchers must overcome. For example, introducing nonnative microbes will always be risky, as foreign rivals may disturb the equilibrium of marine environments. They may also outcompete native microbes, negatively affecting biodiversity, the food web, and nutrient cycles.

Ocean conditions are also volatile. Temperature, pH, and salinity fluctuate, which could impact microbial activity. Deploying microbes in one area may not have successful outcomes in another, even if microbes are targeting the same pollutant. Therefore, scientists must find ways to modify bioremediation efforts to meet each site’s requirements.

Scaling bioremediation to cover the vast sea also presents economic and logistical problems. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates there are 1.335 billion cubic kilometers — or 321,003,271 cubic miles — of water in the ocean. Deploying technologies to reach deep sea contamination may be impossible for some time.

Bioremediation delivers a natural solution to ocean pollution

Marine microbes are a powerful component of sustainable ocean cleanup. These mighty microorganisms use their innate mechanisms to filter and eradicate harmful contaminants across aquatic ecosystems. With the use of cutting-edge bioremediation technologies, their effectiveness has the potential to reach new bounds.

No comments yet