The year 2023 was the warmest since global temperature records were established in 1850, with the average temperature 1.2 °C higher than the 20th century average of 13.9°C. This was also 0.15°C above the previous temperature record of 2016. Additionally, the highest average global temperatures have all occurred in the past decade (2014-2023). There is an 86% probability that at least one of the next four years (2024-2028) will be warmer than the warmest year on record.

This rise in global temperatures will result in far-reaching and severe impacts on multiple facets of our environment, daily activities, and health. It could also increase the spread of infectious diseases and the emergence of new infections.

Surface and groundwater temperatures will also elevate in response to progressing global temperatures, resulting in an increased risk of opportunistic waterborne infections. In this article, we delve into free-living amoebae (FLA), a lesser-known group of pathogens that occur in a variety of freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems. We discuss their role in the transmission of waterborne pathogens and human infection in the context of rising global temperatures.

Free-living amoebae, pathogen engulfment, and transmission

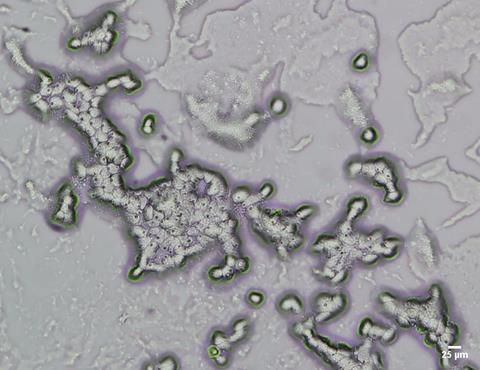

FLA encompasses a diverse group of facultative parasitic protists that occur in a wide range of natural and anthropogenic aquatic environments including rivers, lakes, aquifers, drinking water distribution systems, swimming pools, industrial plumbing, sewer systems as well as soil and air. Biofilms present in aquatic and soil environments have been identified as primary ecological niches for FLA, serving as habitats for attachment and protection, sources of food, and sites for interactions with other microbes. Of the characterised FLA, Acanthamoeba spp. are the most widely distributed, whereas Naegleria spp. are primarily associated with warm aquatic environments. Species of Vermamoeba (formerly Hartmannella), Vahlkampfia, and Echinamoeba have been isolated from both water and soil environments.

Most FLA undergo a biphasic life cycle that consists of metabolically active trophozoite and dormant cyst stages. Under favourable environmental conditions (e.g. warm temperatures between 20-37 °C, presence of bacteria and other small prey, availability of iron and iron-containing metalloproteins) FLA exist in their trophozoite stage feeding on bacteria and other small microorganisms. As principal bacterivores, FLA trophozoites play key roles in modulating community structures and dispersal of bacteria, predominantly in aquatic environments.

Unfavourable conditions such as low nutrients, high or low osmotic pressure, extreme temperatures, or high or low pH lead to the encystation of FLA. Encystation provides high-stress resistance to FLA in harsh environments; some species of Acanthamoeba have successfully been revived following 21 years of encystation under arid conditions. FLA cysts are also tolerant to chlorination and UV irradiation, two of the most used water disinfection processes. It is likely that FLA exist in their encysted form in the nutrient-scarce oligotrophic ground, drinking, and recreational water environments, making them less susceptible to inactivation using disinfections.

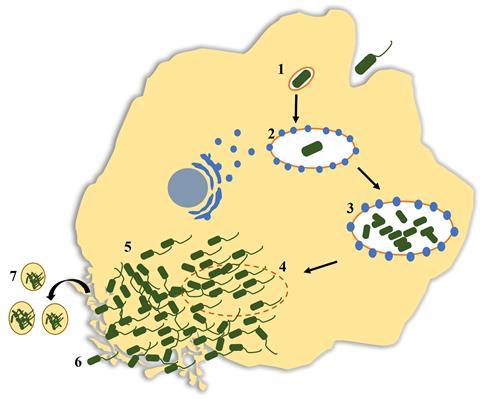

While the majority of internalised bacteria are used as food sources by trophozoites, some microorganisms are able to evade digestion and may proliferate intracellularly. This includes bacteria such as Legionella pneumophila, Vibrio cholerae, non-tuberculosis Mycobacteria spp., Listeria monocytogenes, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa; giant viruses, adenovirus, enterovirus, and species of fungi such as Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida spp., Cryptococcus spp., and Fusarium spp. These organisms, collectively termed ‘amoeba-resistant microorganisms (ARM)’ may also exploit the encystation process of FLA to protect themselves from unfavourable environmental conditions, resuming replication when the FLA begin normal metabolic activity. Studies have demonstrated that numerous species of microorganisms have evolved to resist FLA digestion, with some also capable of intracellular replication, including 102 of the 539 bacterial species classified as human and/or animal pathogens. This common trait seen among bacterial pathogens therefore means that FLA act as reservoirs, enabling their survival and transmission.

Intracellular residence and replication of numerous microorganisms make FLA a unique evolutionary niche that promotes multi-directional gene transfer within and across different kingdoms of microorganisms. This process often leads to the co-evolution of other microorganisms alongside the FLA, leading to the acquisition or loss of genetic elements that directly contribute to enhanced virulence, adaptation to eukaryotic cellular environments, and selection for microbial strains with a broader range of mammalian hosts. For example, there is evidence to suggest that L. pneumophila infections occur due to the structural similarities between amoebae and human alveolar macrophages. It has also been demonstrated that FLA emit small (3-20 μm), membrane-derived vesicles packed with intracellularly replicated L. pneumophila that mostly fall within the human respirable size. Therefore, long-term co-evolution within FLA trophozoites may enhance the overall fitness and virulence of established pathogens and facilitate the emergence of new pathogens, infectious to a variety of mammalian hosts including humans. Predation-mediated adaptations are also believed to result in multi-drug and disinfection resistance among Antibiotic-Resistant Microbes (ARM). As such, FLA not only promote pathogen dispersal but also prime ARM for effective human and other mammalian infections.

FLA in human pathogenesis

Acanthamoeba spp., Naegleria fowleri, Vermamoeba veriformis, and Vahlkampfia spp. can lead to rare but severe parasitic infections, mainly involving the central nervous system of humans and animals. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) caused by N. fowleri and granulomatous amoebic encephalitis (GAE) caused by Acanthamoeba spp., are typically fatal infections affecting both immunocompetent and immunocompromised adults and children, with a higher disease incidence among young men.

Due to their rarity and lack of characteristic symptoms, PAM and GAE can be hard to diagnose and may often be misdiagnosed as other infections. These setbacks in clinical diagnosis combined with the rapid infection progress, limited therapeutic interventions, and resistance of FLA to chemotherapy agents often lead to poor clinical outcomes, as indicated by the high mortality rates reported. Uncertainties regarding the source and time of infection are also contributing factors. FLA can also cause corneal infections leading to keratitis. While Acanthamoeba spp., have been identified as a main cause of Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) infections associated with species of Vermamoeba, Vahlkampfia, and Vannella have also been reported.

Until recently, FLA pathogenesis in humans has only been infrequently reported. However, studies published over the past two decades show an increase in the frequency of PAM, mainly in the United States of America (USA) and the Indian subcontinent. For example, a recent outbreak of PAM in Karachi, Pakistan, between 2015 and 2017, resulted in 24 deaths. Nasal ablution rituals and cleansing practices, common across the country were considered the main cause of this outbreak. It is likely that PAM is more prevalent than is currently reported, particularly in warmer regions where environmental conditions are more favourable for the growth and transmission of N. fowleri.

In the USA, the estimated number of unreported PAM cases is 13 with only 3 cases being reported on average each year. In developing countries, PAM may often be misdiagnosed for bacterial or viral encephalitis or unnoticed due to economic hardship. A rise in AK infections in contact lens users has also been reported, partially due to the heightened prevalence of Acanthamoeba strains in recreational and domestic water supplies in response to the rise in average surface water temperatures. However, the increasing popularity of contact lenses and inadequate lens hygiene remain the primary causes of increased AK incidence.

Climate change impacts on FLA pathogen transmission and pathogenesis

A growing body of literature suggests that the occurrence and grazing behaviours of FLA are favoured by warmer temperatures. Previous findings have reported a higher prevalence of FLA in subtropical and tropical water bodies, compared to those in temperate regions. Seasonal variations in FLA numbers have also been observed, with the highest concentrations recorded over warmer summer months. Additionally, thermal springs have been described as having ideal conditions that favour optimal growth and grazing of thermophilic FLA, including Acanthamoeba and Naegleria spp. This evidence strongly suggests a climate-driven increase in the prevalence and activity of FLA is likely, due to increases in global surface and ground water temperatures.

Robust evidence exists that shows the lethal “brain-eating” Naegleria fowleri are the most susceptible to impacts of climate change, of the FLA types tested. N. fowleri are thermophilic FLA that thrive in warm freshwaters over 30 °C and withstand water temperatures up to 45 °C. Therefore, the rise in surface water temperatures of freshwater bodies due to climate change will likely favour their abundance and prevalence both in natural and anthropogenic waters as well as the interactions with other microorganisms. Waterbodies that were previously too cold for their persistence will become suitable growth niches.

The increase in average global temperatures has resulted in an influx of people using recreational waters, particularly over hot summer periods resulting in an increased exposure and infection risk. This is reflected in the rising number of FLA infections linked to lakes, ponds, swimming pools and other natural and artificial reactional reservoirs. The trophozoites and cysts of N. fowleri and other FLA likely remain aggregated in sediments at the bottom of many natural waterbodies including lakes, ponds, and rivers. Thus, swimming in natural waters and movement of sediment during recreational activities may mobilise trophozoites and cysts of N. fowleri and other FLA, leading to an elevated risk of infection. A reduction in water levels of these reservoirs in arid regions due to limited rainfall may also lead to an increase in concentrations of trophozoites and cysts present within those waters, increasing the exposure risk.

Extreme rainfall and flood events, which are likely to become more frequent due to climate change, have also been reported as sources of N. fowleri infection. Surface runoff following rainfall and flooding events may infiltrate into groundwater reservoirs, resulting in an elevated risk of N. fowleri contamination in drinking and surface water. In a recent molecular survey, 20% of the households that sourced their drinking water from private wells tested positive for N. fowleri gene markers shortly after the 2016 Louisiana flood in the USA. N. fowleri was also detected in domestic plumbing systems in areas affected by the flood. Eutrophication and sedimentation of natural freshwater bodies, caused by meteorological conditions such as droughts, precipitation, and stormwater runoff are also known to promote N. fowleri levels in the environment. Reliance of rainwater storage supplies due to water shortages experienced in arid regions may also play a role in the persistence and dispersal of N. fowleri and other FLA.

According to recent reports, the geographical range of N. fowleri has expanded into states in the USA experiencing climate change-driven temperature increases, characterised by warmer winter seasons. There are also indications that N. fowleri is gradually spreading poleward, to regions where the amoeba was once rare or non-existent. N. fowleri has been recently classified as an emerging infectious agent, because of its climate-induced expansion into previously unaffected regions and the growing incidence of PAM infections. In addition to “wet infections” associated with recreational waters (comprising 93% of PAM cases reported globally), particularly concerning is the rise in “dry infections” caused by inhalation of soil/clay particles contaminated with encysted N. fowleri which have been described in warm/hot regions of the world.

Although studies specific to the impact of climate change on the persistence of Acanthamoeba spp. are sparse, the global prevalence of Acanthamoeba spp. may also be strongly influenced by the changing climate. As an already abundant species established across a wide range of aquatic environments, Acanthamoeba spp. have the potential to further expand their habitats under the more favourable growth conditions resulting from increased surface water temperatures. Dispersal of Acanthamoeba spp. in the environment could pose multiple challenges to public health both due to their inherent pathogenic nature and the ability to function as efficient vectors for diverse ARM implicated in human infection. Therefore, it is likely that an increase in Acanthamoeba abundance and prevalence may also influence the transmission of ARM in the environment, elevating the risk of ARM infections that could be potentially fatal for immunocompromised, elderly, and young children. Some of these infections include legionnaires’ disease, lung infections caused by Burkholderiaceae and M. avium, bronchitis and other respiratory infections, viral gastroenteritis, as well as bacterial/viral/fungal meningoencephalitis. Interestingly, there have been a few reports of bacterial-infected Acanthamoeba trophozoites isolated from patients diagnosed with AK and systemic acathamoebiasis, leading to strong speculation that compounds secreted by these intracellular bacteria may contribute to Acanthamoeba pathogenesis.

Another important issue related to climate change-driven Acanthamoeba dispersal is the potential for the emergence of new pathogenic microorganisms. Warmer temperatures will likely accelerate FLA feeding activities resulting in the engulfment of numerous species of environmental microorganisms. As with any intracellular prey of FLA, these microorganisms will likely undergo important evolutionary processes induced by FLA engulfment, such as selection, gene transfer, and adaptation that may directly influence their virulence and resistance to biocides and disinfectants. Therefore, infections caused by emerging pathogens will potentially be more prevalent, both in humans and other mammalians.

Addressing the emerging FLA crisis: the future of water safety and public health

The ongoing changes in the climate and environment will continue to facilitate the dispersal and prevalence of FLA across both natural and anthropogenic environments. As a result, FLA will likely be present in environmental niches that were previously free of them and their concentrations in drinking and recreational water sources will likely rise. These factors will likely contribute to a future increase in infections caused by FLA, as well as infections resulting from the exposure to the ARM pathogens they harbour, posing a greater risk to water safety and public health. This growing prevalence and activity of FLA and ARM pathogens highlights the requirement for a much better understanding of FLA control and risk mitigation, both in potable and recreational water systems.

Adequate chlorination of potable, recreational, and industrial water is critical for eliminating FLA in both bulk waters and water distribution systems biofilms. However, there is a paucity of knowledge on the effectiveness of disinfectants and biocides against FLA, as the current knowledge is primarily focused on species of gastrointestinal pathogenic protozoa such as Cryptosporidium, Giardia, and Entamoeba histolytica that lead to water-related gastrointestinal outbreaks. There are also inconsistencies in the limited data available on chlorination responses of trophozoite and cyst forms of Acanthamoeba, Vermamoeba, and Naegleria.

Shortage of international guidelines and consensus on accepted chlorination levels for FLA elimination is another key factor contributing to FLA accumulation and dispersal in the environment. For example, it has recently been shown that irradiation of N. fowleri both in bulk drinking water and drinking water biofilms requires a free residual chlorine level >1.3 mg/L, which exceeds the World Health Organization recommendation for drinking water chlorination. Similarly, in France, disinfection treatment is advocated only if N. fowleri levels exceed 100 trophozoites per litre of industrial water. Additionally, there are currently no international standards on the allowable limits of FLA trophozoites in recreational and industrial water. Water monitoring guidelines for FLA contamination and standard protocols for culturing and enrichment are also lacking.

The scarcity of research focused on FLA ecology and biotic and abiotic factors contributing to their geographical spread also imposes critical challenges in mitigating public health risks. There is an urgent need for studies involving clinically significant environmental FLA species such as Vermamoeba, Vahlkampfia, and Sappinia. Investigations should take into account the persistence of these FLA in microbial biofilms and interactions with other microbial species, including the ARM they host.

Investigations for the development and optimisation of both microbiological and molecular methods are essential for the accurate characterisation and identification of pathogenic FLA. For example, conventional microbiological research on culturing, enrichment, and isolation would be highly beneficial for morphological characterisation and establishment of axenic cultures of environmental FLA species. Molecular techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) could be used for rapid detection and quantification of FLA species in samples obtained from environments that may act as sources of amoebae exposure. Genome sequencing approaches are required to determine the diversity and pathogenic potential of these FLA species. Well-described annotated databases containing taxonomically curated reference datasets would also significantly improve the accuracy and efficiency of FLA characterisation.

Despite an increasing number of studies, we are likely still significantly underestimating the human disease burden associated with environmental FLA. With future climate-driven increases in surface and groundwater temperatures, the FLA-associated disease burden is likely to increase further in the coming years. Therefore, there is an urgent requirement for improved FLA control methods as well as public awareness of FLA risks, particularly associated with thermal and/or recreational waters.

Routine monitoring of drinking, recreational, and industrial waters for FLA contamination is critical for the identification of high-risk exposure sources and the implementation of suitable disinfection practices. Sufficient chlorination of water sources and utilisation of combination or alternative treatment approaches, particularly for disinfection of artificial recreational waters where infections are typically acquired, are necessary for the control of FLA numbers. Similarly, adequate disinfection of industrial effluent prior to discharge into freshwater bodies could significantly reduce the risk of FLA contamination in natural recreational environments.

Guidelines should account for the pleomorphic nature of FLA and recommend methods suitable for monitoring and treatment of both trophozoite and encysted forms, with particular consideration of disinfection and biocide tolerance of FLA cysts. Educating water and healthcare professionals on the increasing incidence of FLA and their implications for public health is also needed. Studies aimed at better understanding factors influencing FLA persistence and dispersal in the context of a globally warming climate are essential to improve prevention methods for diseases caused by FLA and the pathogens they harbour and promote.

No comments yet