The UKHSA Food, Water and Environmental (FW&E) microbiology team has published a study on the safety and quality of flour sold in the UK and discovered that eating it raw is not a great idea!

The study highlights the pitfalls of consuming raw flour products such as dough and batter, which may expose the consumer to pathogens including Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli and Salmonella. The majority of the flour tested was of satisfactory microbiological quality, but a small number of samples contained harmful bacteria, so public awareness of consuming uncooked flour and flour products is the take-home message.

Transmission of Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli

The main reservoir for Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) is cattle and other ruminants. Transmission to humans occurs through the consumption of contaminated food and water, exposure to contaminated environments involving direct or indirect exposure to animals or their faeces, or person-to-person spread. The infective dose is low, meaning that very small amounts of contamination may result in illness. Foods associated with outbreaks of STEC include raw or undercooked meat, unpasteurised (raw) milk and cheese made from raw milk, bean sprouts and sprouted seeds, root vegetables, salad vegetables and other leaves, wheat flour, and other flour-type products.

Processing flour

Wheat and other cereal/grain crops may be exposed to pathogens during their growth, due to contamination of the soil or irrigation water or directly from birds and animals. Once a pathogen is on the wheat kernel, it is possible for bacteria to survive during harvest and storage of the grain, as well as through delivery to the flour mill where it is milled into flour. After wheat arrives at the mill, it is mechanically separated to remove foreign materials, after which it is cooled and sent through the milling process. In general, flour produced using traditional milling methods does not go through a validated lethality step (such as heating) to remove any potential pathogens. Because of this, it is possible for pathogens such as E. coli and Salmonella to survive all the way to the finished flour.

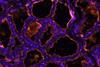

The wheat/grain kernel is composed of three essential parts: bran, germ, and endosperm. The bran layer is the outermost layer of the wheat kernel and therefore carries a greater likelihood of microbiological contamination than the other parts because it’s directly exposed to the environment. Bran and whole wheat flour (which contains all of the components of the wheat kernel) may carry a greater risk of contamination with pathogens.

Baking, cooking, frying, and boiling products containing flour will provide the lethality step to remove any potential pathogens. However, eating flour, raw dough, or raw batter that is intended to be cooked, using flour in items that are not intended to be cooked, such as milkshakes and ice-cream mixes, or adding flour to products after cooking are all potential routes for exposure to bacterial contaminants in the raw flour.

UKHSA flour study

A study was carried out to determine the microbiological safety and quality of flour on sale in the UK and to characterise pathogens isolated from the flour products. Samples of flour were collected by local authority sampling officers and microbiological testing was performed to detect Salmonella spp., generic E. coli and STEC (characterised for the presence of STEC virulence genes: stx1, stx2 and subtypes, eae, ipah, aggR, lt, sth and stp, using molecular methods). Samples were obtained from retailers, caterers, restaurants, and manufacturers across England. A total of 882 samples were collected, including products from at least 40 different countries, with over 50% being produced in the UK. Wheat was the most common grain sampled with 526 (60%) samples received, followed by rice with 53 (6%).

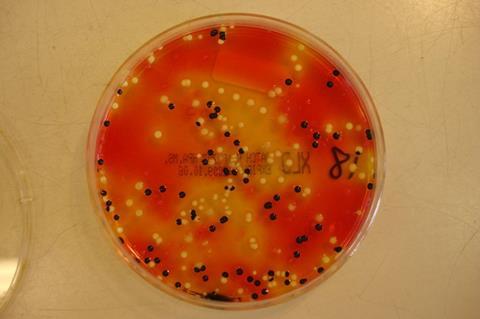

Each flour sample was mixed with a non-selective broth (Buffered Peptone Water), and this homogenate was used to enumerate generic E. coli on selective agar plates as well as detecting the presence of Salmonella and STEC by an overnight enrichment procedure. While serotyping is not performed as part of the initial Salmonella or STEC detection procedure, isolates are subsequently further identified by Whole Genome Sequencing, which provides information on serotype as well as allows determination of any close links with isolates from cases of human infection.

Genomic data were stored in a customised database (Gastro Data Warehouse, London, UK), and pairwise comparisons of SNP addresses were performed on isolates from flour products, cultures from clinical cases that occurred in the United Kingdom, and other isolates from food or the environment. Isolates of Salmonella or STEC were defined as being genetically linked if they fell within a 5 SNP single-linkage cluster and were considered likely to share the same point source if each isolate had a difference of ≤5 SNPs with at least one other isolate within that same cluster.

Results

Amongst the 882 flours sampled, the incidence of Salmonella was 0.1% (a single positive sample was detected that contained multiple ingredients such as flour, dried egg, and dried milk, with the flour being milled in the UK). Molecular characterisation of flour samples revealed the presence of the Shiga-toxin (stx) gene in 10 samples (5 imported and 5 from the UK), of which STEC was isolated from 7 samples. Analysis of WGS results for Salmonella and STEC isolates indicated that none of the STEC flour isolates correlated with previously observed human cases, while the singular Salmonella serotype Newport isolate from the mixed ingredient product was similar to a human case of S. Newport infection that occurred in the UK in 2019. This Salmonella isolate from a wheat grain product with multiple ingredients including dried egg and dried milk, fell within a 5 SNP single linkage cluster of the human case, indicating a common source of contamination/infection. However, no epidemiological data is available on whether this product had been consumed by the affected individual.

A total of 68 samples (8%) contained generic (non-STEC) E. coli at a level of >20 CFU/g. The presence of these types of E. coli indicates the likelihood of faecal contamination in the flour, either from animal or human sources. This may originate from irrigation water, soil, or animals present during crop growth, or unhygienic handling during harvest or post-harvest processing of the crops or flour. Although generic E. coli are not generally harmful, their presence indicates a higher risk of pathogenic bacteria being present, either in the same batches or in past or future batches of the products.

Worldwide outbreaks involving flour

Previous European and North American studies have linked Salmonella and STEC to flour products. Several outbreaks of STEC in North America have been investigated, including an outbreak of STEC O121 and O26 identified in 24 US states associated with the consumption of one brand of flour, with patients admitting to tasting unbaked, homemade dough or batter. In addition, a multi-state outbreak of STEC O26 was linked to raw flour consumption, according to questionnaires which were updated to include flour exposure after one patient admitted to eating raw cookie dough; this resulted in 13 of 21 cases admitting to tasting raw homemade dough or batter. STEC O26 was subsequently isolated from an intact bag of all-purpose flour – the same brand that 11 of 18 patients bought from the same retail chain. Furthermore, a study of wheat flour sold at retail in Canada involved testing 347 pre-packaged wheat flour samples and gave similar results to our study with STEC isolated in six samples. A multistate outbreak of Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis was reported by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), with a link to eating raw dough or batter with cases reported between December 2022 and February 2023. It can be difficult to ascertain if the outbreaks involving raw dough or batter are associated with flour or other ingredients, such as egg products. Despite the evidence of outbreaks linked to this commodity, the risks associated with consuming raw dough or batter are probably underestimated.

Consuming raw dough has the potential to cause serious illness. The results from our study, together with recent flour recalls in Europe and North America show the need for consumer education that flour-based products should not be treated as ready-to-eat. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) run campaigns such as ‘Say No to Raw Dough’, advising people not to consume unbaked dough or batter, not just because the flour has not been cooked but also because the addition of other raw ingredients, such as raw eggs, may pose an infection risk. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also warned against eating raw dough, batter, or cake mixture because of the risk of E. coli from flour, stating that ten million pounds of flour was recalled in 2016 after a mill in Missouri was found to be the probable source of an outbreak. The Food Standards Agency (FSA) in the UK has concurred with the FDA’s recommendation to avoid consumption of raw flour after outbreaks of food poisoning in other countries caused by Salmonella and E. coli.

Message to consumers

Results from this study suggest that there may be a need for safety messaging on commercially available packages warning that flour and raw flour products, such as cake or pancake mixes, are considered raw ingredients and should not be consumed without cooking. Overall, most flour samples tested were of satisfactory microbiological quality, but consumer awareness is important to minimise infection from the small proportion of flour products that may be contaminated with pathogenic bacteria.

No comments yet