UniGreenScheme founder Michael McLeod opens up to The Microbiologist on how a student side hustle trawling car boot sales has evolved into a burgeoning business that trades surplus lab equipment to researchers in need.

If you love your lab equipment - which let’s face it, we do - there’s nothing sadder than seeing perfectly good machines tossed into a skip because they’re now surplus to requirements.

A few years back, that’s exactly what might have happened - but increasingly lab managers are finding ways to refurbish unloved equipment and in many cases are selling them onto scientists who are delighted to take delivery of a microscope or fume extractor that just needed a little TLC to give it a whole new life.

At the forefront of this drive for sustainability is UniGreenScheme, the brainchild of Michael McLeod who transformed a student side hustle into a pioneering enterprise which is fast breaking new ground.

Clear out

The idea is simple - collect second-hand equipment from university labs that are having a clean-out, refurbish it if needed and then sell on to another lab that can make use of it - returning a share of the profits to the original owner.

Not only does it mean the equipment gets a new lease of life, but the original lab can plough much needed profit back into their work, while the buyer picks up equipment that they might not be able to afford new.

One of the first universities to sign up to the service was Bristol, around six or seven years ago, Michael explains.

“We were probably 45 minutes drive away from the university - we are on the other side of the bridge, so it’s actually pretty close,” he says.

“We were still just trying to get interest to prove that universities will be interested in this, and they came to our site, had a look at our operations and were happy with everything that we were doing.

“They were very proactive actually - they spoke to a lot of their departments and found people might be interested in the service. Steve Gaze and the Biomedical Sciences technical team are very passionate about sustainability in what they do.

Spring clean

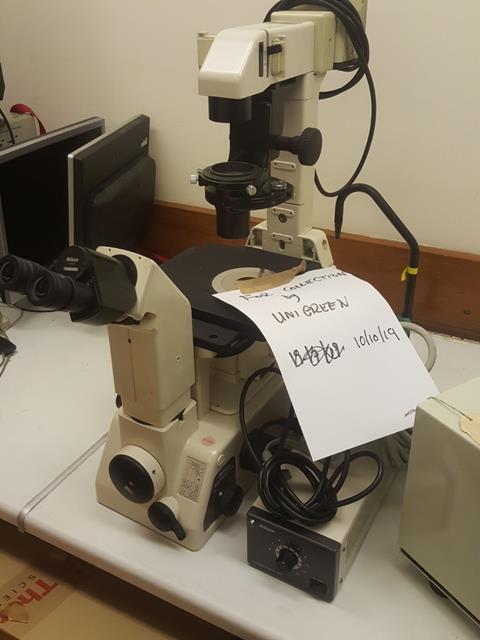

“They did kind of a spring clear-out type thing initially, and then we just did quite a few collections of equipment after that. It would be everything from cryostats to little microscopes and stuff - often it’ll be something like a microscope that really needs a complete overhaul, but it’s still quite a nice microscope.

“I think we have one example where, perhaps a student had damaged the gears and it was quite an expensive fix but well worth doing for a microscope which was worth a few thousand pounds when it’s running.”

Michael also mentions a cryostat that had just been sitting in a lab and the university earned £1,000 when UniGreenScheme sold it.

“It went to a facility in France to carry out proteomics research, so you can imagine that the savings for them buying used equipment and being able to carry out research is enormous,” he says.

“We had seven spectrometers go to a lab in Germany. We had quite a lot of these very basic university spectrometers - there were 15 of them, and 10 of them ended up going to the same lab facility in Derby. So they go to a range of private sector and research institutes and places like that.”

Used goods business

Now 31, Michael launched UniGreenScheme at the age of 23 when he was a postgraduate student at the University of Birmingham, working on cellular signalling in muscle in the Sport Science Department.

At the same time he had launched a used goods business from a self storage container selling on low-value items he had acquired at car boot sales to make some money to supplement his student income - everything from Monopoly board games to old PlayStation One games.

“I’d go to car boot sales and spend £500 in a weekend. You could just look up the prices of things - I wasn’t breaking some new trend or anything, but it was keeping me busy and I was trying to earn a little bit of money on the side while studying.

“At the same time I was trying to think of ways to grow this thing to more than just a little side hobby and then I went to this lab clear-out one night and found this one item that was worth £600 quid and it was going straight into a skip.

“One of the first items we sold was an oxygen analyzer from the sports metabolism lab and it went off to an Italian university. Another item we sold was a fume extractor from a welding shop, but they’d never wired it in. It had never been used and it had been sat there for a long, long time.

“It was a little bit shocking seeing this stuff being chucked away and the building manager there was a really nice guy, and his attitude was like, I don’t want to throw it away, if you can do something with it, then fantastic.”

Sustainability team

At the time a number of departments were merging together and there wasn’t space for all the equipment.

“I started approaching the university more centrally to say, Can I do this as a service as a startup business? And as part of the Entrepreneurship Society there, I got help to speak to the university’s sustainability team and they were like, well, actually, this is onto something a little bit,” Michael says.

“I was going to University of Warwick and University of Nottingham as well, because I was on the Midlands Bioscience Training Partnership, and I saw exactly the same problem in the labs there, just mass spectrometers and stuff everywhere, not being used.

“So we came up with the idea to collect, store and sell redundant equipment through a company called UniGreenScheme and we formed a company in January 2015.”

It wasn’t until March 2016 that they started doing collections, but by now Michael’s stepfather had come on board, and the Universities of Oxford, Glasgow Caledonian and Aston all signed up within the first few months.

“There’s this constant cycle where they get a new grant and buy some new equipment, but the older equipment maybe works ok, or perhaps they want to hold it as spare parts because the power supplies match or whatever. And so it goes into a cupboard, or in some cases, it just sits on the lab bench, and it just gathers dust for years and years and years, taking up space,” MIchael says.

“I’ve seen a biological safety cabinet that was biannually serviced for eight years and not used during that whole period of time. The costs of this are phenomenal.”

Skip full of microscopes

Michael remembers one student telling him that their university had had a clear-out the previous week and filled a skip with microscopes.

“The student body is not willing to tolerate that anymore, so it’s very much on the agenda for universities to make sure that they’re being sustainable with how they dispose of equipment,” he says.

“The industry has changed enormously in the years that I’ve been involved in it. When I first started most universities had one person and a quarter of their job was sustainability. Now you’ve got teams of 20- 30 staff just focusing on sustainability.”

And as times have changed, the business has grown - 15 members of staff now work at the main site in Caerphilly in South Wales, with three staff at a secondary site in Dumfries, launched a few years ago with support from Zero Scotland.

The Scottish site collects from the likes of the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, Aberdeen, but their reach has expanded southwards to work with Newcastle, Manchester, Liverpool and York. Along with Wales, Oxford, Reading, Bristol, Bath, Warwick, Nottingham, King’s College London, Imperial and UCL, Michael estimates that UniGreenScheme covers over half the sector.

Learning curve

He admits it was a steep learning curve at the start as the used lab equipment market was quite small and fragmented.

“There wasn’t like a huge place we could go to learn, and in many ways, it was kind of just get this stuff, stick it online, sell it and then see what happens,” he says.

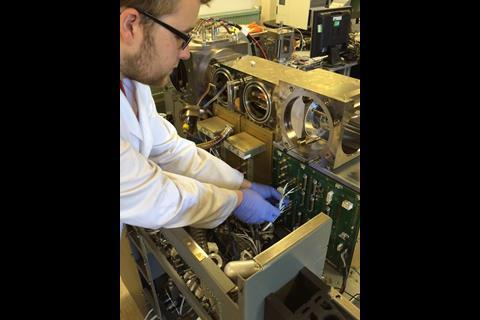

“But now we’ve learned and developed and got much more advanced sales channels. So we’ve got some really good engineers for both internal and external, for looking at lasers and vacuum systems and software and all sorts, so that we can basically refurbish equipment and sell it for the end user.

“We’re looking at a lot of international universities as buyers, and universities in the UK as well, and lots and lots of private sector companies.

The biggest international markets for the company are the US, Europe and Australia, with sales to Vietnam, China and Japan.

“I think what is really exciting is the potential scalability, because when I go and visit the site, it seems kind of crazy, looking around at the scale of it. We’ve got 30,000 square foot of floor space, and something like 3,000 pallets and it’s enormous,” Michael says.

Tip of the iceberg

“I know it’s cheesy to say, but it’s the tip of the iceberg because there are so many universities we’re not working with, and even the universities we are working with, we’re working with a fraction of departments.

“Even in those departments, you’re dealing with a handful of contacts and you see medical schools where they’ve got 1,500 staff and you’ve got three contacts and they’re still giving you a truckload of equipment every month.

“So we could grow this comfortably five to tenfold, realistically. We’ve done some projects with the NHS, we’ve done some projects with quite large private sector companies, we’ve done projects with a lot of research institutes and facilities for the MRC, NERC and BBSRC as well. So that’s our very immediate focus.

“I’m also hoping that we can continue to improve the technical capabilities, but I really want us to get to a point where we can repair and refurbish the whole spectrum of products to the point that we’re potentially helping other people getting equipment refurbished.

“We’ve done that a little bit with some of our clients, where some of the labs we work with, they’re getting quoted £2,500 pounds for repairs to a fan from the manufacturer and it’s an off-the-shelf part that costs £25.

“Ultimately our goal is about keeping equipment in the loop, getting equipment reused and trying to run science as sustainably as possible in many ways. So there’s a lot of room to grow and continue to expand.”

Next big idea

Looking back, Michael admits he did enjoy his time in the lab, which came to just under three years, but he had to make the difficult decision to abandon the research..

“It was unfortunate but I was in a position where it’s like I’ve got this opportunity or this opportunity,” he says.

“But I feel like I’m really contributing to the sector in a way that I couldn’t have done. When I think about it, we’ve sold 700,000kg or 800,000kg of equipment that we’ve managed to get reused.

“Think about the amount of research that we will have supported, not just in what we’ve paid the university which I think is about £400,000.

“I know the people buying this equipment, I know they are underfunded and are trying to carry out research. And I also think about how the next big idea might not come from a billion pound university but somebody working in their garage with a UniGreenScheme microscope - I find that quite exciting!”

No comments yet